Bone Biology and Physiology: Dynamic Interplay of Strength and Function

Bone is in a constant state of remodeling, resorbing older tissue and forming new matrix through the coordinated activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. This process adapts to kinematic stresses, tuning to mechanical forces, repairing microdamage, and local tissue environment. The role of bone, through its multifunctional, hierarchical structure, lends itself to more than a rigid, unresponsive scaffold.

Hierarchical Engineering: From Molecular to Macro

- Nanoscale: At the nanoscale, bone is a composite biomaterial made primarily of type I collagen fibers and hydroxyapatite mineral crystals. Collagen provides tensile strength and flexibility, while the mineral phase lends compressive strength. These components are intricately interwoven, creating a staggered, brick-and-mortar-like architecture that helps to dissipate energy and resist fracture. Non-collagenous proteins (proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and glycoproteins) and bound water molecules also play crucial roles, mediating mineralization, regulating cell activity and influencing mechanical behavior. This is the foundation of bone’s toughness and serves as the interface for cellular signaling and early tissue organization.

- Microstructure: The microstructure of bone exhibits its nanoscale assembly into larger, functional units. Building from the nanoscale level, bone can exist in two main forms: 1) lamellar bone: highly organized, typically in band/sheet structure, and mechanically strong; and 2) woven bone: rapidly formed and structurally disorganized. Moreover, bone structure is differentiated by formation type, primary or secondary. Primary bone is distinguished in three forms during the development phase: Primary Lamellar, Plexiform, and Primary Osteons. While Secondary Bone is defined as remodeled bone. Organization governs bone’s adaptability and turnover, enabling remodeling response to mechanical stress and/or injury.

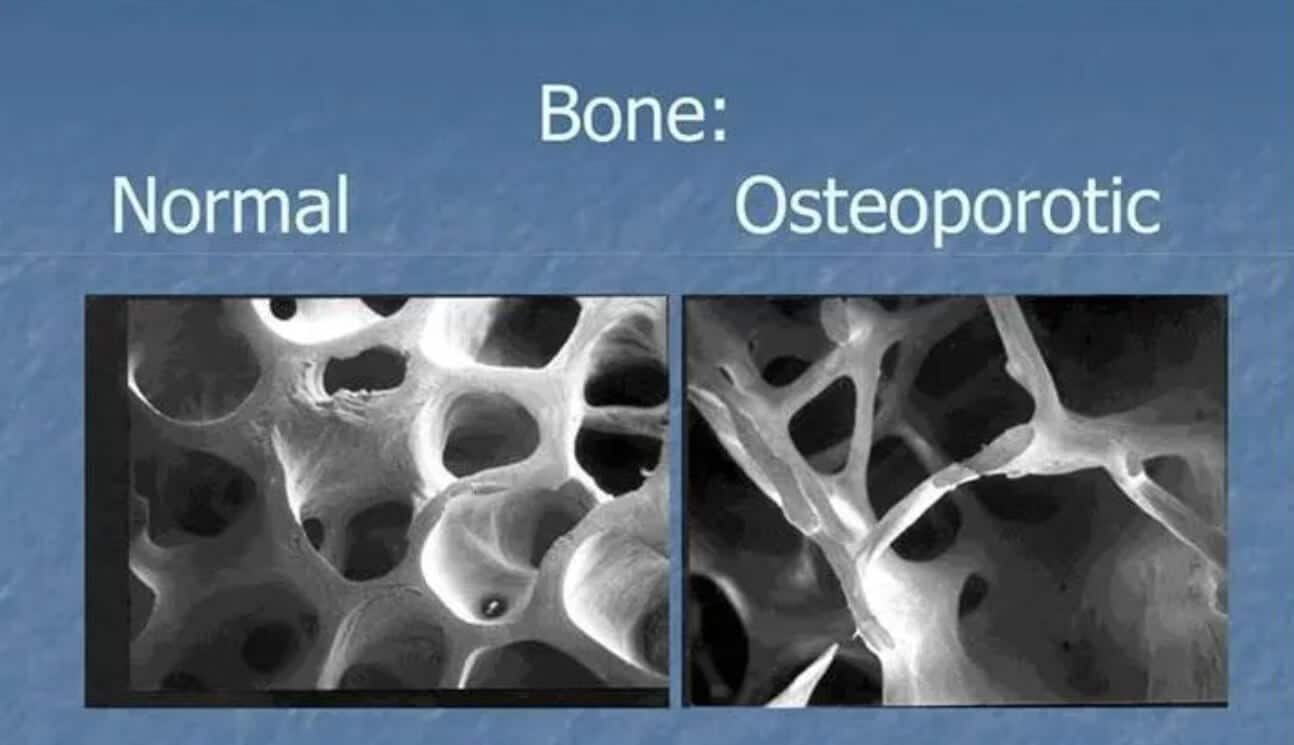

- Macroscale: From the nano and microstructure, the macroscopic lens of bone is categorized by its porosity, location, and function into cortical (compact) and cancellous (trabecular or spongy) bone. Cortical bone forms the dense outer shaft, or diaphysis, that provides rigidity and protection. Whilst cancellous bone, found in the metaphyses of long bones and vertebrae, has a porous structure that supports metabolic activity and fluid flow. At this scale, bones serve for structural support and movement, reservoirs for calcium and phosphate, and protection for marrow and vital organs. The four remodeling surfaces (periosteal, endocortical, intracortical, and trabecular) define where bone can be deposited or resorbed, making the macroscopic architecture critical to surgical planning, implant fixation, and long-term biomechanical performance.

Mechanical Adaptation: Responding to Strain

The varying levels of structure provide bone’s capacity for mechanical sensation and adaptation. Through mechanotransduction, the conversion of mechanical forces into biochemical signals, osteocytes detect changes in mechanical loading and initiate signaling cascades that instruct osteoblasts and osteoclasts to adjust bone formation and resorption accordingly. This ensures that bone formation and resorption are spatially targeted and load dependent. When subjected to repetitive stress, bone strengthens by increasing density and structural organization; conversely, reduced loading, such as in immobilization or off-loading, leads to bone resorption. This continuous fine-tuning maintains skeletal strength, tissue repair, and optimizes architecture based on functional demand. At the nanoscale, collagen and mineral interfaces adapt to dissipate forces; at the microstructural level, remodeling targets regions for maintenance; and at the macroscale, bone architecture is optimized for functional demands such as load-bearing and movement. This adaptability ensures that bone remains strong, responsive, and structurally optimized, particularly during post-surgical recovery or orthopedic intervention.

Fracture Healing: Cellular Events

Fracture is the loss of anatomic continuity and/or mechanical stability of the bone, commonly associated with falls, car accidents, contact injuries, and endocrine factors relating to loss of bone density. Repair after fracture is a unique process that aims to restore bone structure and function. Reflecting on the aforementioned hierarchical principles underlying normal bone structure and mechanical adaptation, the body initiates a cascade of events (hematoma formation, inflammation, soft callus and hard callus formation, and eventual remodeling) at the endochondral and intramembranous interfaces. The coordinated response reconstructs the bony tissue from the molecular level to full structural integrity. At the nanoscale, platelets aggregate to form a hematoma then degranulate to release growth factors locally. In response to changes in the microenvironmental milieu, periosteal mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) proliferate and quickly differentiate into osteoblast for the purposes of collagen synthesis, cartilage template formation (soft callus), and mineral associated proteins. At the microstructural level, woven bone is initially formed through soft tissue callus calcification (hard callus development), later replaced by organized lamellar bone through remodeling. Macroscopically, the alignment, stability, and load distribution across the fracture site guide remodeling pathways via mechanosensitive feedback from osteocytes. This multiscale repair mimics developmental processes, relying on both biological signaling and mechanical forces.

Conclusion

The bone framework is not static; it continuously responds to mechanical forces and biological cues. In the surgical context, bone must be manipulated, reinforced, or regenerated to stabilize fractures, place implants, or address degenerative conditions. Adapting a clinical approach to heal and remodel bone’s living scaffold will influence functional performance. To learn more about Sanara MedTech products, please visit Our Surgical Products | Sanara MedTech Inc. .

References

- Florencio-Silva R, Sasso GR, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:421746. doi:10.1155/2015/421746

- Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:455-498. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721

- Chao, EYS, Aro, HT. Biomechanics of fracture repair and fracture fixation. In: Leung, P.C. (eds) Current Practice of Fracture Treatment. 1994; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78603-7_2

- Einhorn TA. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(355 Suppl):S7-S21. doi:10.1097/00003086-199810001-00003

- Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(1):45-54. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2014.164

- Burr, DB, and Allen, MR. Basic and Applied Bone Biology. London, Academic Press, 2014. Chapters 1-2, 6, 9-10.